- Sep 26, 2025

A 2025 View of Rare Earth Materials and Global Trade

The contemporary economy's silent powerhouses are rare earth elements. Rare earth elements (REEs) support sectors influencing the future of the world, from the magnets in electric vehicle (EV) motors to the alloys used in fighter planes, and from smartphones to renewable energy systems. In terms of crustal quantity, as per Asia import data by Import Globals, they are not uncommon, but their processing challenges, supply chain concentration, and geopolitical power make them economically significant.

Global manufacturing and energy security are significantly impacted by the changing rare earth trade flows, production dynamics, and regulatory frameworks as 2025 draws near. Let's examine the current status of the international trade in rare earth commodities, taking a look at supply, demand, price, reserves, and potential hazards.

The Significance of Rare Earths in International Trade

Neodymium, praseodymium, dysprosium, and terbium are examples of rare earths that are not uncommon in nature, despite their name. The concentration of commercially viable deposits and the difficulty of converting them into forms that may be used are what define them as "rare." Based on China Export Data by Import Globals, China has always had a significant edge in rare earth manufacturing since it necessitates sophisticated chemical separation, unlike basic metals.

Rare earths are essential for vital military systems as well as "green" sectors like wind and electric vehicles. China Import Export Global Data indicates that they are key commodities due to their dual-use nature. They are increasingly being viewed by governments throughout the world as assets linked to industrial strategy and national security, rather than merely as raw commodities.

Worldwide Production and Stockpiles

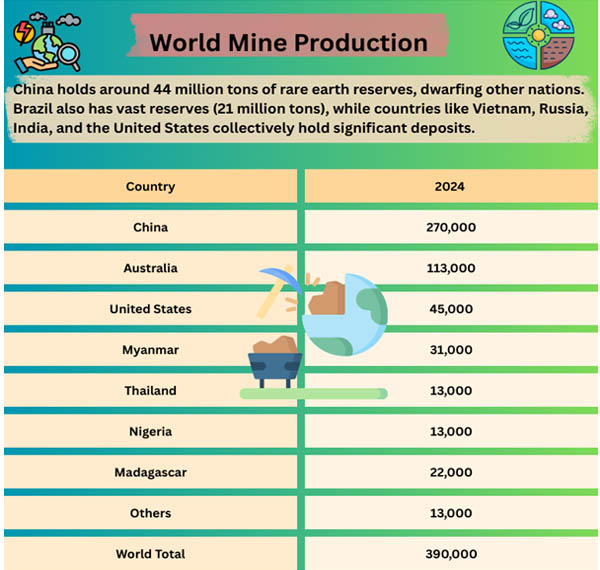

Rare earth mine output has risen continuously worldwide, with an expected 390,000 tons produced in 2024. As per Australia Import Export Trade Data by Import Globals, with about 70% of the total output, China continues to be the undisputed leader, followed by the US and Australia. Production in Southeast Asia, especially in Thailand and Myanmar, has fluctuated as a result of environmental regulations and governmental crackdowns.

Rare earth mine output has risen continuously worldwide, with an expected 390,000 tons produced in 2024. As per Australia Import Export Trade Data by Import Globals, with about 70% of the total output, China continues to be the undisputed leader, followed by the US and Australia. Production in Southeast Asia, especially in Thailand and Myanmar, has fluctuated as a result of environmental regulations and governmental crackdowns.

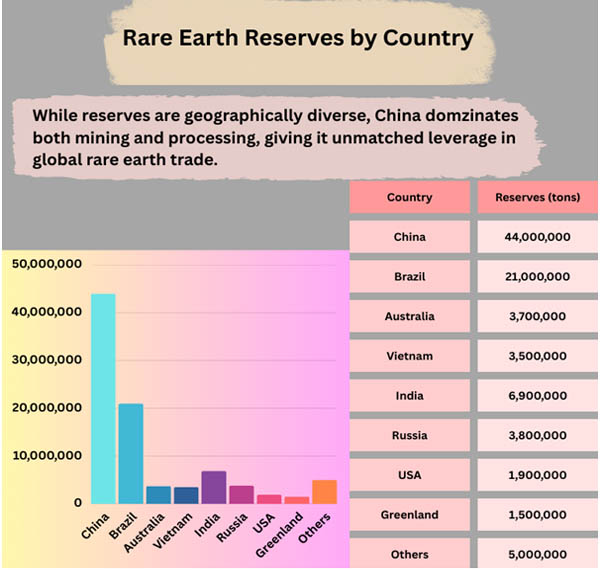

The image painted by the reserves is equally telling. China has far more rare earth deposits than any other country, with an estimated 44 million tons. Brazil also has enormous reserves (21 million tons), while the United States, Russia, Vietnam, and India all have large resources.

Trade Patterns and Dependency on Imports

Another level of reliance is exposed by trade flows. About 55,000 tons of rare earths were shipped by China in 2024, a 6% rise in volume but a sharp drop in export value as a result of declining prices. According to Europe Import Custom Data by Import Globals, imports of rare earths into the European Union decreased by about 30% in 2024 as a result of diversification initiatives and a decline in industrial demand.

Even after increasing domestic production to 45,000 tons, the US still imported over 80% of its rare earth metals and compounds. Japan Export Import Global Trade Data indicates that China accounted for more than 70% of U.S. imports between 2020 and 2023, with Malaysia, Japan, and Estonia following closely after.

Market Signals and Price Trends

During the height of supply chain disruptions in 2022, rare earth prices spiked, but they have since dropped. China Import Trade Analysis by Import Globals indicates that production grew and demand decreased, prices for magnet oxides like terbium, dysprosium, and neodymium dropped dramatically by 2024. The decline in terbium and neodymium prices serves as an example of how cyclical demand, particularly from EVs, may alter prices. However, volatility is still considerable and can be triggered by changes in legislation, limits on exports, or unexpected discoveries.

Geopolitical Influence and Policy

Governments have realized that rare earths are power tools rather than just commodities. China has strengthened state control over commerce by tightening export licensing and data-reporting regulations. Based on Europe Export Data, the Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA), introduced by the European Union in 2024, established aggressive goals: by 2030, at least 10% of extraction, 40% of processing, and 25% of recycling must take place within the EU. Dependency on any one nation for imports cannot be greater than 65%. The United States is funding initiatives in collaboration with Australia and Canada and has advocated for local processing facilities. In an effort to stabilize its rare earth sector and draw in private investment, Australia is investigating price-support methods. These changes in policy point to a rush to diversify supplies and lessen reliance on China.

Drivers of Demand in All Industries

Despite ongoing short-term volatility, demand for rare earths is expected to increase.

- Electric Vehicles (EVs): Neodymium and dysprosium are essential components of permanent magnet motors.

- Wind Turbines: Neodymium magnets are necessary for the efficiency of direct-drive turbines.

- Defense Systems: Certain REEs are needed for radar, sensors, and precise guiding.

- Glass Polishing and Catalysts: They are two conventional yet sizable end-use categories.

- Long-term expansion in clean energy and sophisticated electronics guarantees continuing rising pressure on rare earth usage, as suggested by Import Globals in USA Import Data, even in the face of weaker demand in 2024.

Opportunities and Risks

There are particular hazards in the rare earth market:

- Supply Concentration: The biggest concern is still China's processing supremacy.

- Price volatility: Demand shocks or export regulations can cause prices to fluctuate rapidly.

- Environmental Concerns: The high ecological costs of mining and processing might impede growth.

- Opportunities: Based on Africa Import Trade Statistics, with the help of offtake agreements and state-backed funding, nations like Australia, the United States, and even Africa are in a strong position to increase their share of the supply chain.

Toward 2030

The rare earth trade will probably be more varied than it is now, although not entirely balanced, by 2030. Important developments to keep an eye on include:

- Non-Chinese Magnet Supply Chains: North America and Europe be able to establish mine-to-magnet integrated supply chains.

- Geopolitically sensitive, heavy rare earth elements (REEs) (Dy, Tb) are still hard to replace.

- Recycling Growth: Although economies are still difficult, EU objectives could boost recycling to 25% of supply by 2030.

- Strategic Stockpiles: To protect against supply disruptions, countries may be accumulating rare earths in greater quantities.

Import Globals is a leading data provider of China import export trade data. Subscribe to Import Globals to get more global trade details!

FAQs

Que. Are rare earths really rare?

Ans. No. They are abundant in Earth’s crust but rarely found in concentrated, mineable deposits. Their rarity lies in economic extraction and processing.

Que. Why is China so dominant?

Ans. Because it controls not only mining but also the midstream processing and refining that other countries lack at scale.

Que. What is the EU doing to reduce reliance?

Ans. As per Europe Import Export Trade Analysis, the EU’s Critical Raw Materials Act sets firm extraction, processing, and recycling targets to reduce dependence on China by 2030.

Que. Which industries depend most on rare earths?

Ans. EVs, wind energy, defense, and electronics are the largest consumers, with neodymium and dysprosium especially critical.

Que. Where can you obtain detailed USA Import Shipment Data?

Ans. Visit www.importglobals.com or email info@importglobals.com for more information on up-to-date data.