- Jan 16, 2026

How Venezuela’s Oil Exports To The USA Have Evolved In 2025-2026

Heavy, sour grades that complicated Gulf Coast refineries can operate well to get the most diesel and other high-value products. But the story hasn't been a simple "return to normal" in 2025–2026. Instead, there has been a stop-start cycle caused by licensing, compliance risk, shipping limits, and changing U.S. policy goals. Then, in early 2026, there was a sudden turn toward more structured, deal-driven flows.

The difference between these two times is what makes this one stand out. In 2025, there is volatility and interruption, but in early 2026, there is re-activation under stricter political and commercial choreography, with specific traders, specific approvals, and a clearer (though still fragile) corridor for barrels to reach U.S. buyers.

Why the U.S. Still Cares About Barrels from Venezuela

As per USA Import Data by Import Globals, the U.S. doesn't have a lot of crude oil, but it does choose which kinds it wants. Many refineries on the Gulf Coast were built or improved to handle heavy sour crude. If those refineries can't get enough of the correct grades, they have to use Canadian heavy, Mexican Maya-type grades, or heavier Middle Eastern blends instead. Each of them has its own pros and cons in terms of price, logistics, and yield.

Venezuelan grades like Merey-16 can be appealing because they fit with how refineries work and can occasionally give better product yields than other options. In early 2026, dealers even said that Merey-16 was being sold at a smaller discount to Brent than Canadian heavy barrels. This showed that U.S. refiners thought the barrels were worth something in the current market.

The 2025 Pattern: Strong Start, Collapse in the Middle of the Year, and Partial Recovery

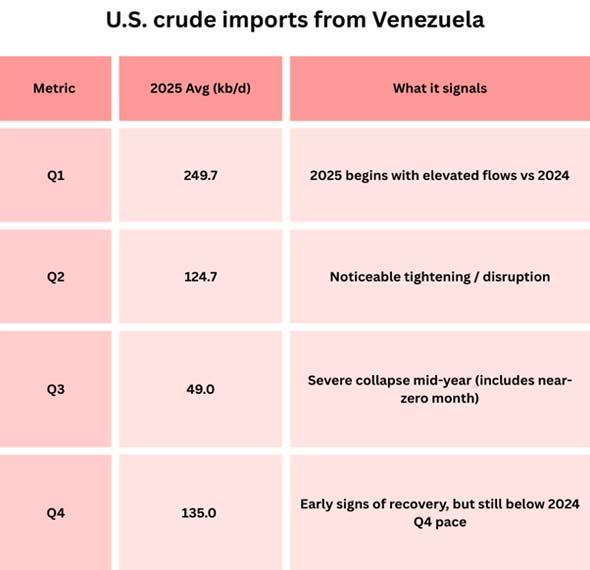

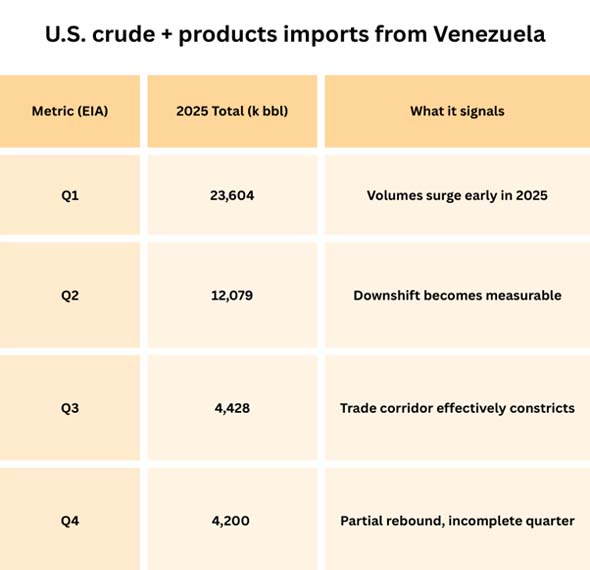

Import data is the best way to see "evolution" without any mess. According to U.S. official data on crude oil imports from Venezuela (thousand barrels per day), the year 2025 starts off strong, but then there is a big decline in the middle of the year that comes near to zero and then a small rise later in the year.

What caused the 2025 Volatility?

In real life, flows from Venezuela to the U.S. are rarely "pure market." Based on Venezuela Export Data by Import Globals, they rely on what is allowed, how payments are made, who will handle the barrels, and whether shipment and insurance can be arranged without breaking the law. When rules get harsher or the risk of enforcement goes greater, barrels don't only relocate to new places; occasionally they don't even make it to the U.S. at all, or they take other paths and wind up in various markets.

Reports on Venezuelan exports showed that by the end of 2025, Venezuela was still sending a lot of goods to other countries. But how much flowed to the U.S. depended on which companies could safely carry crude oil while following the rules.

The 2026 Pivot: Exports Based on Deals, Trading Houses, and a Channel That Is More Focused

The system looks very different in early 2026. Instead of "routine" commercial trade, the flow looks more like regulated re-entry, with explicit agreements, oversight procedures, and specified middlemen.

Some important things that were reported in early January 2026 are:

- Organized Sales as Part of a Big Deal Between Two Countries: According to USA Customs Data by Import Globals, the U.S. finished the first round of Venezuelan oil sales, which were worth around $500 million and were part of a larger $2 billion deal. The money from these transactions is kept in U.S.-controlled banks.

- A big possible Export Allowance: Reporting that authority has been given for the shipment of up to 50 million barrels to the U.S. suggests that this might be a major supply conduit if it happens.

- Chevron's main Function (and Possible Growth): In the past few weeks, it was said that Chevron was sending about 100,000 to 150,000 barrels of Venezuelan crude oil to the U.S. and that it was also in line for a bigger license that would let it produce and export more oil.

- Venezuelan Merey-16 was said to be offered at a smaller discount to Brent than West Canadian Select at Houston, making it competitive for Gulf Coast refiners.

What "Evolution" means in this Case

As per USA Import Data by Import Globals, early 2026 looks less like an open market and more like a negotiated supply lane than the uneven pattern of 2025. There are limits on who can lift (specific companies/traders), how funds move (controlled accounts), how much can move (deal ceilings like 50 million barrels), and how quickly the U.S. can broaden permissions (license changes).

This doesn't ensure stability—managed corridors can still constrict quickly—but it does indicate a shift from the "fragile restart" dynamic of 2025 to a more formal and scalable structure.

Pricing: What Makes Venezuelan Crude Better Than Other Heavy Barrels

According to Venezuela Export Data by Import Globals, pricing behavior is a little but crucial point in 2026. Traders said that Venezuelan heavy oil was being offered to refiners at prices that were significantly higher than those of Canadian heavy in the Gulf Coast market (i.e., less discounted to Brent). Refiners may prefer improved product yield economics, compatibility with refinery equipment, or logistical/availability advantages at the margin.

If the flow that has been reopened stays steady, Venezuelan barrels can put pressure on heavy grades that are competing with them, especially those that use the same coking refineries.

Things to Look Forward to in 2026

Length and breadth of a license: As per Venezuela Trade Data by Import Globals, short licenses lead to "surge then stop" trade patterns, while longer and clearer licenses allow business to continue in the core sectors. Operational recovery in Venezuela: Even with authorization, production reliability depends on the availability of diluents, upgraders, and maintenance.

Conclusion

The easiest way to explain how Venezuela's oil exports to the US changed from 2025 to 2026 is that they went from being random and hard to follow in 2025 to being more deal-driven and organized in early 2026. The EIA's Import Data shows that there were robust figures at the beginning of 2025, a decline in the middle of the year, and a partial recovery. Then, in early 2026, it looks like the reopening will have a lot more trades, fewer means to pay, more traders, and the prospect of more licenses being granted out.

If this more formal way of doing things maintains the same in 2026, Venezuelan oil might once again become a bigger and more dependable component of the Gulf Coast heavy slate. But the most important thing about 2025 is still true: this corridor is never simply for business, and if regulations or enforcement change, it might get smaller very quickly. Import Globals is a leading data provider of Venezuela Import Data.

FAQs

Que. Did Venezuela really send more oil to the U.S. in 2025?

Ans. The U.S. bought more goods from other countries in early 2025 than it did in all of 2024. However, the year was very unpredictable, with a big drop in trade in the middle of the year and just a little rise thereafter.

Que. Why do U.S. refiners seek Venezuelan crude oil in particular?

Ans. Heavy sour crude is what many refineries on the U.S. Gulf Coast are best at, and Venezuelan grades can be a good match with good yields.

Que. What was different in 2026 than in 2025?

Ans. Reports from early 2026 show a more structured framework with big agreed sales, managed proceeds, and the possibility of license growth, instead of weak "on/off" flows.

Que. Is it possible for Venezuelan crude to take the place of Canadian heavy in the U.S.?

Ans. It can at the margin, especially when prices are better for Venezuelan grades and Gulf Coast refiners have some leeway. But it all relies on how steady the supply is and how stable the policy is.

Que. Where to get detailed Venezuela Trade Data?

Ans. Visit www.importglobals.com.